- Home

- Lilith Saintcrow

Cormorant Run Page 2

Cormorant Run Read online

Page 2

Who wouldn’t be keyed up this close to a Rift? Even the assholes who’d been predicting Intelligent Life Somewhere Else had been floored by the Event, and all the kooks suddenly “proven” right about UFOs had a field day until the true extent of the casualties sank in. Not the civilians vanished when the Event happened, but the ones who went into the Rifts right after, thinking they were going to be pioneers or some shit. In the end, all the emergency planning in every municipality, county, province, state, country, and continent had only managed sticking-plasters over bleeding gunshot wounds. Excising whole cities from the map was a messy business.

Permission to land was granted with a burst and a crackle of transmission code and the transport leav began to sink gently, gyros whining and its cells glowing with Mata curve differentials. Svin didn’t shut her eyes until the slugwall slid out of sight behind a bulky concrete-and-sealed-glass building. A few moments after that, the bump of landing jolted all the way through Svin’s bones, and since she wasn’t shot in the back she decided the Reg70 behind her had either some trigger discipline or a couple dry nerves left. Or maybe she had to finish praying before she shot one of Satan’s minions.

Once the bubble lifted, the 70 holstered her gun but kept her knee in Svin’s kidneys.

It would, Svin thought, be easy. Pitch forward, getting her legs up behind her, use the 70 to push off against, hope not to chip a tooth or dislocate her shoulder on concrete, but if she did pop her shoulder out, the restraints would be easier to wriggle. Once her hands were in front of her, they might get her from the towers but at least she could get this particular 70’s neck snapped before the rounds went through Svin’s body. It would depend on how drunk the tower watch was.

Staring at the slugwall’s slow, opalescent sheen for hours at a time did bad things to the inside of your head. It was axiomatic that the only way to keep the guards doing it was an alcohol ration, and with the mounted guns, you didn’t need accuracy. Just the willingness to shoot even at shadows.

Svin let the moment pass. Let the 70 haul her from the leav, let her entire body go slack. Landed in a heap on pavement blast-cleaned by leavcells and containment chemicals, getting a good look around as she fell and closing her eyes again to fix it all in memory. A standard horseshoe of an Institute, the walls lead-webbed concrete sandwiches, its open end full of U-shaped levvy slots—just lines of white paint on the concrete, nothing fancy, a total of three sleds resting on blocks for moving heavy shit. The actual levvy bays would probably be on the south side, and—

The 70 hauled her up again by the back of her paper-thin prison jumpsuit. “You little shit. Stand up!” The black helmet was fogged on the inside—someone was doing some heavy breathing. Another shake, Svinga’s head bobbling on her neck, as if she were only partly conscious.

Whoever was watching might get the idea this particular 70 had beaten the crap out of her prisoner in transport. And the bobbling gave Svin a chance to observe more of the layout.

One of the cargo doors on the northern face was opening, and a flurry of movement started. Scientists? Other rifters? A flash of light—someone wearing glasses, maybe? Had to be vanity, anyone who could afford it got ocular nowadays. Svin let herself stay nice and limp, making the 70 work for every step.

There. The bottom of the U—the eastern wall, facing the k-zone* and the blur—opened up a couple of black gaps as well, and security forces came spilling through. The uniforms were black, but the red piping at the shoulders showed they were sardies, frontline troops instead of jumped-up faux-polizei.

Red-eye stripe, yo’ ass is wiped, the saying ran. Right after the Event sardies were hurried into uniform in case it was the prelude to an attack. During the Crash, they were government mercenaries—distinguished from private mercenary armies only in the matter of paymaster and the quality of their rations, and sometimes not even the latter.

If they had this many sardies just sitting around, it must be a bigger Rift. Which narrowed the list.

Always look, Ashe said, years ago. Look. Think. Then and only then do you move even a finger. Even an eyelash.

Svinga sensed the 70’s intent to drop her a split second before it happened and went down again, rolling violently sideways as if the guard had kicked her. Yeah, it was a standard Institute, built a few years after the Event but before the Crash, when funding was sloshing around and everyone was terrified. Another piece of evidence saying a bigger Rift. She’d been hooded for the first few legs of transport, so she had very little idea of where she was. Across the ocean from Guan, that was for sure.

Which was great. The further away, the better.

Now she had the general layout, she could guess at the rest. Know your ground, Ashe always said. So Svinga lay on the cold hard landing pad, curled around herself as if it hurt to move. It did, a little, but that was life. If you didn’t expect it and hold yourself in readiness, your expiration date would amble up and bite you before you were even close to ready.

That was when she caught sight of the scorch. A looping, blackened path from the blur in, and just like everything to do with the Rift, it looked … different. Wrong. A normal person wouldn’t be able to tell just how, and would look quickly away, maybe with their stomach clenching a bit and a cold bead of sweat forming right at the base of their spine.

Svinga stared. The mark was too black, too thick, and she gapped her mouth, quick sipping breaths. You had to taste things.

There was no hint of anything but exhaust and cold weather. Just a faintly obscene streak burned into pavement, heat-rings rippling at its edges.

“Stand down!” someone was yelling, probably at the 70 behind her. The transport goon began shouting something muffled, and there was a crackle of live stimsticks.* She was probably still trying to explain when the first one smacked against her flexphase armor.

Flexphase didn’t have anti-stim padding, which made it lighter. An advantage for a transport dick, until it wasn’t.

Svin lay very still, ears and eyes open, as if she had just gone over the blur and hit the ground, waiting to see which direction danger would come from. Her fingers curled whiteknuckle-tight over the cableplug that fastened into the 70’s belt. It was the channel output jack, and without it, the onion-reeking Yarker bitch was shouting into the wind. The sardies would think she was dustsick,* or crazed by being too close to a rifter, and if there was one thing about frontline troops, it was their tendency to beat the shit out of a target first and find out why it wasn’t responding later.

It was, Svinga decided, not a bad way to start her first real day out of prison.

5

OUR AGREEMENT

The one-way mirror was filthy with dust and flyspotting, which distorted the view of a sweating concrete room lit by a buzzing fluorescent tube. Thin, nasty light played over a thin woman slumped in a metal chair bolted to the floor. Shackled, deadfish-pale hands rested on the interrogation table; her maroon prisoner’s jumpsuit was just this side of threadbare and the flextag with her number and barcode at her left breast lay flat and almost frayed out of legibility. Her pointed chin dropped slightly while ropes of dirt-matted hair swayed forward, then jerked upward, regaining lost ground. Either she was trying to stay awake or she was bobbing to atonal, rhythmless, wholly internal music. Grime lodged under her bitten-down fingernails and along the cuticles, and every once in a while, when her head jerked back up, the tip of her nose showed just as fish-belly as her wrists.

Prison pallor. You saw the sun for an hour a day in max, rain or shine, but not at all in solitary.

“That’s it?” Kope’s nose wrinkled as he arranged his uniform cuffs. It was a big, generous nose, and its twitches signaled his feelings—or what he wanted you to think his feelings were—at every possible opportunity. “Shit.”

“You asked for a good rifter.” Zlofter pulled irritably at the cuffs of his shiny new suit, too, perhaps not realizing he was mirroring the larger man. His slick black pompadour almost glowed in the dimness, and his silver

earpiece was the latest little gift from the Rift’s depths, a high-range Aurovox. Probably a thank-you present from his corporate masters, a shiny collar making sure they could buzz him at any moment with marching orders. A glorified leash.

Kope’s disgusted snort echoed in the concrete corners. “And your little knob-polishing buddies send us a washed-out felon? We could have gone into town and picked up a few dozen of those by ourselves.” He had to be careful to sound just irritated enough. DynaKrom had no shortage of people or funding to throw at whatever their rifters brought out, and government agencies couldn’t hope to compete. Especially when standing orders were NINO—nothing in, nothing out. They wanted to “map” the smaller Rifts first.

That fucking decision had probably come out of a committee. It had idiot written all over it.

He should have gone into private security instead of the sardie-hole. He’d been telling himself that for years, but his contract was signed and fucking set, and there was nothing to be done but make the best of a bad pile of fertilizer, as his grandfather would have said.

So it was begging for scraps under the guise of “cooperation,” and if there was one part of his job that made Kope want to set the entire fucking building on fire and piss on the flames, it was the sucking up necessary to get even this halfass kind of quasi-legal support. Of course, if they suspected exactly what he was after, they would probably take over his whole installation, and even though he could cheerfully gut the place, it was still his. And he was still capable of oiling the levers right to get what he wanted. The proof of that was sitting in the room on the other side of the mirror.

When this place was built, there was still hope some civilians had survived inside the Rifts and were waiting for rescue. So, thoughtfully, the design had included a couple of debriefing rooms. There was an ancient commjack in the wall in front of them, at knee height. He could have scavenged some equally ancient camera to tape this, if he’d wanted to. God knew there was probably one old enough in the storerooms.

Zlofter’s greasy mouth pursed. “How many of those would have been trained by Rajtnik?”

Anticipation had begun, beating right under Kope’s overworked heart. He had to go through the motions, make sure this little asshole thought he was dispensing largesse instead of falling right into a carefully prepared plan. “Do you mean trained by or fucked by? The Rat wasn’t very selective.” I need a connection to the Rat, and I need it disposable, he’d told Zlofter. There was only one possible fit, and he’d let the man arrive at that conclusion himself.

“You didn’t even bother to look at the file.”

Kope restrained the urge to throttle the whining bastard. It wouldn’t look good. “Tatiana Pajari, goes by Svinga, thirty-three, born in Sobzardio, near the Sbardo Rift. Emigrated at sixteen on a false passport, went offgrid until she showed up working the Birmingham Rift with Rajtnik. Pops up again near other Rifts, makes a name for herself, then gets arrested two years and change ago for running poppers illegally near Shasta. Would have been just a thirty-day sentence in lo-sec clinical, but she killed two of the four arresting officers and crippled a third for life. Course, the officers were used to beating every goddamn smuggler to a pulp to teach ’em not to get caught. Didn’t bargain on a rifter, and there’s some suspicion that a local warboy* had paid to have her—or one of the Rat’s crew—erased. They put her in Guan† and threw away the key.” Rifters didn’t do well in general population, so they’d stuck her in solitary a lot. The file hadn’t said whether she’d needed “interrogation.”

“I stand corrected.” Zlofter’s prissy little mouth didn’t relax, though. Nor did his manicured hands, the left one bearing a tastefully expensive chaxalloy‡ ring. “I don’t blame you, though. She does look a little …”

“She looks like a dust-sniffing whore,” Kope supplied. The only thing missing was raw nostrils and a disintegrating septum. By the time they got that thin, dustsluts—especially the males—started to show the collapse right in the center of their face. Nosers, some called them. Sniffbabies. Or, one of Kope’s favorites, holeyheads. Like Yarkers, sniffing after God.

The rifter’s head jerked up, as if she’d heard him. It dropped by degrees, again, following whatever weird rhythm-free music was playing in her brain.

“I can always have her sent back, Kopelund.”

Now was the time to let Zlofter think he’d won. Not too easily, but not too hard, either. Kope shifted his big shoulders under his ill-fitting gray uniform jacket. Finally, grudgingly, he assented to the inevitable he’d been working for all along. “Fine.” Now the other man would add what he thought was a trap’s closing jaws to the situation.

Right on time, Zlofter opened his oily mouth. The bastard was nothing if not predictable. “And of course, we would like a look at anything she brings out.”

Sure they would. Kope kept his face a blank wall, with just the faintest suggestion of a bad smell reaching his several-times-broken nose, which obediently twitched once. “That’s our agreement.”

“Very well.” The corporate man checked his sleek silver atomic chrono. “I have a meeting in town. Ping me if you need anything else.”

Kope just nodded, as if he didn’t know Zlofter was just going to visit the Rabak, drink all afternoon, and send the Institute the tab. Maybe the little bastard was celebrating getting one over on him and pocketing the finder’s fee Kope had scraped out of the budget to pay for this piece-of-shit, washed-up rifter. He barely heard the door shut, Zlofter making a squeaky little remark to the guard outside, or his own breathing.

Once he was gone, Kope grimaced, his face screwing up afresh before it smoothed and he leaned forward, studying her intently through the dirty glass.

Still skinny. Still wearing prison pallor, and that filthy hair hanging in lank matted ropes. The tip of her long nose peeked out again, and the black-and-white Guan ID headshot in the file showed a remarkably ugly woman. The nose was huge, the mouth too broad, the teeth barely fitting in, and her eyes protruded like watery eggs. Her shoulders jerked a little as her chin rose again, and Kope shook his head.

He was hoping Zlofter couldn’t smell his excitement. This was the rifter Kopelund had hoped for, Ashe the Rat’s protégé, the one Ashe had wanted to get out of lockup before she went in with Bosch and Gunther and three expendable sardie troublemakers for the Cormorant.

Well, the prodigal was here now.

Kope bared his own very large teeth in a white, predatory grin, smoothing his graying hair back.

Time to meet his new acquisition.

6

DEADNAME

Tired.

Her head kept dropping, and she would surface when the fluorescent’s buzz overhead changed a fraction or when the balding, heavyset guard outside the interrogation room’s door shifted his weight, his uniform whispering against itself. It was cold, but she’d learned long ago not to shiver—waste of energy, gave away your position, and was a distraction. All things you couldn’t afford past the slugwall.

Or in prison.

The grime under her fingernails was black, her skin cringing from the light. She mapped the blue veins on the back of each hand as if they were a slice of Rift she had to traverse, a trancelike alertness requiring her to look, learn, look again, look again. If she went deep enough, she might be able to see the slight changes as her blood pressure shifted, the blue lines creep-crawling like a worm or a scuttlesnake.*

That reminded her of Ashe and their fourth trip into Birmingham. Or was it the fifth? Her, the Rat, and Connie the Goof with his golden head shaved. His hair was lucky, but the lice had finally gotten too bad, because he was a filthy mother-fucker with running sores on his scalp from scratching too much.

Maybe that was why the first half of that particular trip had gone bad. The sound as the Goof was snatched because he didn’t drop fast enough, yanked into the air by a passing shimmer, the scuttlesnake following the grav-flux’s looping path jerked free of grassy dirt too and snap-crunching as i

t fused with Connie, each shape struggling for primacy before the shimmer dropped them both in a spray of blood, brains, bone fragments, and fragrant glaslime.* Vicious gleaming shrapnel from the scuttlesnake’s spinal column had peppered the entire area, but at least Connie’s death had been quick.

Sick fear, the tremble in her hands, and a squirming sensation of serves you right for not listening, Goof, and crawling forward on her belly after Ashe, testing each hand- and toehold before committing herself, barely daring to stand even when the shimmer was gone and Ashe said come on up.

Behind the dusty, flyspotted mirror on the wall to her left, breathing presences loomed. Probably whoever had yanked her out of prison. Maybe Ashe had worked a deal, though that wasn’t like her. Let it drop and on to the next was her philosophy, and a good one if you could stomach it. Kept the Rat alive and going into the blur, instead of liver-rotted, rotting in a cell, or exploded in a shimmer.

Svin exhaled softly. The cuffs weren’t too tight. If she wanted to, she could yank a hand free. It would only cost a little skin, but she was still ankle-shackled to the chair. Wasn’t worth it.

Not yet.

So she waited. Lots of life was just hanging around. Wait for a client, wait until the blur moved, wait until the shimmer or the crawling sense of danger passed, wait until someone who had money was at home to buy. Once you got comfortable with the idea of crapping wherever they left you, it was surprisingly easy. You didn’t even have to wipe, if they were just going to keep you in a box. Just pick a corner and tune the smell out. If they didn’t feed you, though, you didn’t shit. Or so Fuller Ginch, the only convict who’d bothered to talk to her in Guan, always said.

Incorruptible

Incorruptible Finder (The Watchers Book 6)

Finder (The Watchers Book 6) Steelflower in Snow

Steelflower in Snow Dante Valentine

Dante Valentine Redemption Alley-Jill Kismet 3

Redemption Alley-Jill Kismet 3 The Iron Wyrm Affair

The Iron Wyrm Affair The Demon's Librarian

The Demon's Librarian The Hedgewitch Queen

The Hedgewitch Queen Redemption Alley

Redemption Alley Flesh Circus

Flesh Circus Saint City Sinners

Saint City Sinners Unfallen

Unfallen Heaven’s Spite

Heaven’s Spite The Devil s Right Hand

The Devil s Right Hand Roadside Magic

Roadside Magic Steelflower at Sea

Steelflower at Sea Agent Gemini

Agent Gemini Blood Call

Blood Call Agent Zero

Agent Zero In The Ruins

In The Ruins Atlanta Bound

Atlanta Bound Hunter, Healer

Hunter, Healer Hunter's Prayer

Hunter's Prayer Roadtrip Z_Season 2_In The Ruins

Roadtrip Z_Season 2_In The Ruins Wasteland King

Wasteland King Pack

Pack Flesh Circus - 4

Flesh Circus - 4 Trailer Park Fae

Trailer Park Fae The Bandit King h-2

The Bandit King h-2 Working for the Devil

Working for the Devil Pocalypse Road

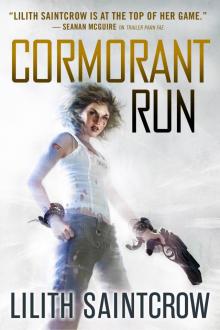

Pocalypse Road Cormorant Run

Cormorant Run Dante Valentine Book 5 - To Hell and Back

Dante Valentine Book 5 - To Hell and Back Desires, Known

Desires, Known Roadtrip Z (Season 3): Pocalypse Road

Roadtrip Z (Season 3): Pocalypse Road Afterwar

Afterwar Selene

Selene The Society

The Society The Hedgewitch Queen h-1

The Hedgewitch Queen h-1 Night Shift jk-1

Night Shift jk-1 Dead Man Rising

Dead Man Rising Dead Man Rising dv-2

Dead Man Rising dv-2 The Iron Wyrm Affair: Bannon and Clare: Book 1

The Iron Wyrm Affair: Bannon and Clare: Book 1 Saint City Sinners dv-4

Saint City Sinners dv-4 Heaven's Spite jk-5

Heaven's Spite jk-5 Beast of Wonder

Beast of Wonder Hunter's Prayer jk-2

Hunter's Prayer jk-2 The Damnation Affair

The Damnation Affair Steelflower

Steelflower The Red Plague Affair: Bannon & Clare: Book Two

The Red Plague Affair: Bannon & Clare: Book Two The Iron Wyrm Affair tb&ca-1

The Iron Wyrm Affair tb&ca-1 Flesh Circus jk-4

Flesh Circus jk-4 Jozzie & Sugar Belle

Jozzie & Sugar Belle Night Shift

Night Shift The Bandit King

The Bandit King![Hunter, Healer [Sequel to The Society] Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/05/hunter_healer_[sequel_to_the_society]_preview.jpg) Hunter, Healer [Sequel to The Society]

Hunter, Healer [Sequel to The Society] The Devil's Right Hand dv-3

The Devil's Right Hand dv-3 To Hell and Back dv-5

To Hell and Back dv-5 Angel Town

Angel Town The Red Plague Affair tb&ca-2

The Red Plague Affair tb&ca-2 Redemption Alley jk-3

Redemption Alley jk-3 The Damnation Affair (the bannon & clare affairs)

The Damnation Affair (the bannon & clare affairs) Working for the Devil dv-1

Working for the Devil dv-1