- Home

- Lilith Saintcrow

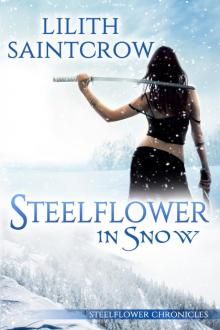

Steelflower in Snow

Steelflower in Snow Read online

Steelflower in Snow

Lilith Saintcrow

STEELFLOWER IN SNOW Copyright © 2017 by Lilith Saintcrow

Cover art copyright © 2018 by Skyla Dawn Cameron

Trade Paperback ISBN: 9780999201312

Mass Market Paperback ISBN: 9780999201381

Ebook ISBN: 9781950447077

* * *

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the author, except for the use of brief quotations in a book review.

For Skyla Dawn Cameron.

Because without her, it wouldn’t be.

Contents

1. Certain Proprieties

2. First Snow

3. We Shall Meet It

4. The Eater

5. The Death Gate

6. Not Something I Wish to Propagate

7. A Quiet Gathering

8. Battlefield Mercy

9. A Tricksome Business

10. A King Now

11. Emrath

12. A Guest is Sacred

13. A Deepwyrm's Eyes

14. Other Than I Was

15. No Unlearning

16. Many a Song

17. Risk Wherever We Land

18. I Can Be No Less

19. Argue With a Duel

20. Meant to Be Whole

21. Arrivals

22. Taking Kalburn Too

23. Strike the Weak

24. Children or Slaves

25. His Great Lumpen Self

26. Aid, No Aid

27. Before a Night Patrol

28. Below the Ridgeline

29. Cob-Colored Mare

30. Clash-Slither Music

31. Blood-Tinged Tickle

32. Make the Bait Sweeter

33. Common Knowledge

34. Sink Alone

35. Not Today

36. Climb to Me

37. Deepcrack Freeze

Glossary

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Also by Lilith Saintcrow

Certain Proprieties

It began to drizzle, a chill dispirited prickle-rain Clau sailors call moonbreath, for they believe her the source of all cold as the sun is all heat. I hunched, watching the paved expanse of the North Road from the shelter of a cranyon tree’s bulk, its branches not yet naked but full of vibrant-painted, dying leaves. Antai simmered in its cup, down to the liquid glitter of the harbour, smoke-haze frothing like the foam on well-whisked chai. The ponies—shaggy beasts with wise eyes and mischievous dispositions—were much smaller than any I would have selected. Redfist, however, pronounced them the best choice for the North in this season. There were no Skaialan draft horses in the markets; the farmers in the hinterlands prizing them too highly to send them down into the bowl. Our red barbarian giant was too big for the ponies, but his legs had carried him from Hain to a battlefield, then back to Vulfentown and over the sea. Once we were through the Pass, he said, he could find a mount if he wished.

A little further up the Road, well out of even crossbow range, a slatternly tavern leaned upon its exhausted stable. It was slightly flea-bitten, but safe enough for Redfist to sit with a tankard for a while. A few hours along the road was the furthest I had gone in that particular direction.

Just as the Danhai plains were the furthest west I’d gone from the Rim. I was too exhausted to suppress the shudder that always went through me when I dwelled too long upon those two years.

Even through the chill mist, I could sense the heat of approaching murder. I stepped away from the tree, my dotani ringing from its sheath. We were lucky the commission had not been high enough to interest a daykiller. Those are almost impossible to halt, and their price reflects as much.

No, this black Dunkast perhaps did not understand Antai’s Guild, or there was a reason he wished Redfist murdered in the dark. He had paid in pale Northern gold, not the good ruddy gloss of Shainakh Rams, or so the smoking, stinking, reeking wreck of an assassin had told me. The hand that had carried the gold was none other than Corran Ninefinger’s; the blond giant could have been simply a stupid catspaw. Soon enough they would hunt him down, too, if they had not already. Redfist did not say what had prompted his blond fellow giant to come south.

Put your worries away, Kaia. They are not needed here.

I took my position in the middle of the North Road. Later, mud would creep across the stones in slow rivers, and here above the bowl, away from the harbor’s breath, it would freeze. A pale cloud puffed out of my mouth, drops of water flashing through it, and the shadows moved on the other side of the crumbling arc of walls that had been witchery-strong in the Pensari’s day. It had been a long while since the great city had needed its shell upon the hilltops.

Dusky rainlight turned them into cloak-wrapped enigmas, kerchiefs over their mouths, their hoods dripping with the moisture. Hands folded inside wide sleeves, three of the Guild eyed me. I returned the favor.

One of them would be a representative of the clan who had sent last night’s courtiers. One would be sent directly from the Head and the Council, to make certain proprieties were observed. The third would be a witness from another clan, one most likely not allied with the first. No doubt I would have to pay double-dues next tithing-season—if I returned. The commission was bound to have a provision for interference, and hopefully it was not large enough to tempt anyone outside the walls with winter fast approaching.

We eyed each other, and I tensed, my dotani rising slightly. Scuffling sounds, high fast breathing, and movement behind them. Two shadows, with a third held awkwardly between them.

They held thiefcatchers, long wooden spars age-darkened and banded with iron. Each had a prong, like a yueh rune that had lost half a leg to battleground injury; the shorter half ended in a hocta-knot around the prisoner’s neck, the spare loop snugged under the armpits. The longer was attached to the girdle, and walking inside that contraption was unsteady at best and bloody at worst.

They call it the Chastity, for the short spikes on the inside.

She was forced to her knees before the three senior Guild members, and a muffled curse told me who it was. A chill spread over me.

Even if I forgave Sorche Smahua’s-kin, there was still this to face. If fate had been kinder, she might have chosen a sellsword’s path instead of a thief’s clan, or had it chosen for her. Even if the first assassin had taken it upon herself to avenge Sorche’s thiefmother, the Sorche as the elder should have restrained her. Not only had she robbed the clan of the investment her little thiefling had represented, but the clumsiness of said little thiefling had warned me to be wary and perhaps cost the Smoke—or another clan—part of a fat commission.

It was not the potential death of a Guild member in good standing they would punish her for. It was the loss of profit. There are many temples in Antai, many gods from both the hinterlands and abroad, but the one who rules beneath, above, and throughout them all had been disobeyed, and would take due vengeance.

One of the elders moved forward. A murmur was probably the delivery of the sentence in old Pensari, and a long silence showed where that word, the one that was never uttered, fit into its contours. The sibilants carried, and a breeze shook the cranyon tree’s leaves. A rattle as some fell, the wet gleam of a blade.

“Mother!” Sorche cried, just before the most senior clanmember, the one in the middle, wrenched her head back. She might have fought, too, but the other two had her arms and the thiefcatchers were braced. A high spattering jet of arterial blood as her throat was opened, and I did not look away.

Some are children

for their entire lives. Hot, rancid fluid boiled in my throat. There was no chai that would wash away the taste.

They watched as I strode for the wall-line; I felt a burst of concern—D’ri, wedged in the cranyon tree’s upper reaches with his bow—as I moved forward and into bow-range from the crumbling stone. My left hand moved for a pocket, and I halted just on the other side of the invisible boundary.

I held up the Shainakh red Ram, its shine visible even in this darkness. The Moon hid her face behind a passing cloud, and I flicked the gold off my fingers in the thieves’ way, the metal describing a high spinning arc before a dark-gloved hand blurred out to catch it.

“For her pyre,” I said, as clearly as I could, in tradespeak.

One nodded, a fractional dip of the muffled head. They could have thrown her body over the wall. This way, at least, her spirit would rise on the smoke and join her thiefmother’s, in whatever afterworld the two of them might share.

I turned my back on them, but I did not sheathe my dotani. I walked, steadily, for the cranyon again, its bole a wet pillar and its outline blurring with moisture. The thin piercing rain had soaked into my braids; they were heavy once more, my neck throbbing with tension. My teeth ached as well—I forced myself to loosen my jaw, despite the risk of the bubble in my throat bursting.

If it did, I decided, I would swallow it.

And that was how we left Antai.

First Snow

The Road remained easy enough, though it began to climb on the third afternoon. Broad farmland on either side lay under a pall of mist for the first five days as we wended north and vaguely west from Antai, the Lan’ai Shairukh receding further with every step. Big red-furred Rainak Redfist did not speak much, striding all day with uncomplaining and deceptive placidity. His bearded chin jutted thoughtfully, and the beads braided into his face-pelt clicked every so often. When we stopped at waystations he did more than his share, as if in apology for the disruption to our plans.

Darik rode silently, and the ponies liked him a great deal. He had already begun preparing their hooves for ice, teaching them to be familiar with his touch.

And I? I found myself thinking much upon the past. Uncomfortable, certainly, and never to be recommended unless one is longing to learn a lesson or two from experience. Even then, it is always better to look forward.

There was no minstrel-strumming at our nightly fire, no child to chatter or sing Vulfentown drinking-songs in a high sweet unbroken voice, none of Janaire’s soft merriment or Atyarik’s easy companionship with another s’tarei. I had grown…accustomed to our little troupe, as I had to few others during my travels. Perhaps it was merely a measure of how long we had endured each others’ company.

At least they were safe in Antai. They would spend the winter there in something like comfort, and spring would see our reunion, if all went well.

I did not think it would, but what else could I do? I had given my word, and Redfist could not go alone. Not after I had spent so much effort keeping his flour-pale hide in one piece since picking his pocket in a Hain tavern.

Traveling-calm descended upon our trio. Redfist often hummed Skaialan melodies, his swinging strides marking the rhythm; on the second day I began to hum as well, a wandering counterpoint that sometimes slid through remembered childhood songs. D’ri was content to listen, scanning the far horizon with a line between his coal-black eyebrows. Whether he expected trouble or was simply lost in his thoughts, I did not ask.

Instead, our talk was all of commonplaces—the ponies, where to rest, the likelihood of the mist or the rain breaking in the afternoon, what piece of gear needed repairing or modification. The towns became villages with hostels instead of inns; the taverns became smaller and quieter. For days the blue smear of mountains on the northern horizon came no closer. It was late in the season for caravans to start, but we found evidence of their passing everywhere, especially in the waystations where the firewood was restocked and the straw full of still-green fislaine to keep the mice away.

The Road went only halfway through the Pass, they said, and after that you were left to forge your way without Pensari poured stone underfoot. Even the Pensari did not encroach further upon the Highlands, and it cannot have been because of the ice alone; the giants of the north are held to be fierce and unruly. I found Redfist tractable enough, though I could well imagine how an entire room of ale-loving, bearded mountains might cause concern to smaller folk.

Not to mention the smell, if they were as ripe as Corran Ninefinger, or Redfist himself when I found him.

It was almost a moonturn before the sharptooth mountains drew close enough to oppress and the Road began to rise more sharply. The house-roofs rose as well, peaks meant to slide rain and snow away like a courtesan’s robe down his shoulders. The hinterland folk are closemouth and drive hard bargains, but they are honorable enough when travelers mind their own mouths and manners. They call that mountain range Amath-khalir, an ancient conjunction that means rocks which do not lose their snow in summer.

No doubt the Pensari had other names for it.

We made good time, with the ease of sellswords used to long journeys. At least we had not been in Antai long enough to soften. Sometimes we continued half the night, relying on Redfist’s memory of the hamlets and their contents along the ribbon of Pensari stonework. Their roads were not the broad curving avenues of the Hain or the flat-cobbled Shainakh streets; no, everywhere the Pensari ruled the crossroads are spokes of a wheel and the ribbon-roads straight as could be, only barely altering course a degree or two for some stubborn knot in the landscape. Most of the time, they slice straight through such silly things as hills, or leap across torrents with their sturdy poured-stone bridges the Antai have lost the secret of making. There are stories of folk who may make stone live and grow as green things do, but I have never traveled far enough to see that witchery. In G’maihallan, such a thing could be done, but would perhaps be considered tasteless, and a waste of Power besides.

The frosts came, and soon enough the ground hardened. Carts on the road, heaped high with fodder or late produce, became fewer. The travelers we met were all streaming south, and no few of them must have laughed at the fools traveling in the opposite direction at that season. Then there were no carts and precious few travelers for a day or so, and the bite to the wind brought a rosiness to what little of Redfist’s cheeks could be seen under red fur.

“Strange,” I remarked at a nooning, as the ponies drank their fill from a clear, cold, fast-running streamlet already rimed at its edges. “There are no Skaialan traveling this road.”

Redfist, scrubbing at his face and the back of his neck with a rag from my clothpurse, gave a short bark of amusement. “Noticed that, did ye?”

I glanced at D’ri. His hair, neatly trimmed in the Anjalismir s’tarei style I remembered from my youth, was wind-mussed, and he looked as if he enjoyed the chill. At least it was not a heaving deck, and we had no disagreements to speak of.

“Is it usually otherwise?” my s’tarei asked.

“In this season? Those who can get through the Pass might not be able to return, but there’s always a few.” Redfist sounded grim. “Karnagh’s probably closed tighter than a miser’s wife-basket, though. Corran gave a hint or two.”

“Did he.” And when were you going to share the hints with me, barbarian? I stroked the red-and-white pony’s neck, enjoying the texture. Gloves and furs would soon be necessary, but at least the taih’adai had taught me of the warming breath and a few other ways to keep ice from a G’mai. The nightly lighting of the fire without sparkstones had mixed results—either I could barely produce an anemic flame, or the pile of tinder evaporated into ash after a ball of hungry orange fury devoured it wholesale. Still, I generally managed to call a fire into being without singing a roof or either of my companions, and that was well enough.

“Never thought it would come to this.” A heavy sigh bowed Redfist’s wide shoulders. He ceased at his scrubbing, looking at the mounta

ins as if they held an answer to some riddle not yet voiced. “He was a cousin. Knew his father.”

“He may not have known everything in the commission.” I ran my fingers through thickening horse-fur, the vital haze of heat and life from the pony all but visible. Every living thing cloaked itself in that trembling energy, Power begging to be tapped, released, shaped into harmony and brilliance. A continual wonder; how did other adai deal with the distraction? “But he did deliver it to the Guild.”

“How much?” Redfist dropped his blue gaze to the rag of Hain cotton, working it around his callused fingers.

It had taken him a long time to ask. There was no reason not to tell him. “Two hundred pieces of pale Northern gold, each stamped with a wolfshead sigil.” A princely sum, indeed. The Guild would not scruple to return it unless the commission was withdrawn, either, so our barbarian could not return to Antai just yet.

“So. At least I am worth something.” Redfist paused. “And new coinage. The mines…” A shake of his head, his red hair pulled back and tied in a club with a leather thong. “Tis a fool’s errand, this. The Pass may well be closed.”

“Do you wish to turn back?” I turned my gaze away, in case he could not admit it while watched. The trees had changed; instead of those who disrobed every autumn, those who drew their green finery higher against the cold surrounded us. They are secretive, those dark masses, and their pungency can fill the head just like mead.

Incorruptible

Incorruptible Finder (The Watchers Book 6)

Finder (The Watchers Book 6) Steelflower in Snow

Steelflower in Snow Dante Valentine

Dante Valentine Redemption Alley-Jill Kismet 3

Redemption Alley-Jill Kismet 3 The Iron Wyrm Affair

The Iron Wyrm Affair The Demon's Librarian

The Demon's Librarian The Hedgewitch Queen

The Hedgewitch Queen Redemption Alley

Redemption Alley Flesh Circus

Flesh Circus Saint City Sinners

Saint City Sinners Unfallen

Unfallen Heaven’s Spite

Heaven’s Spite The Devil s Right Hand

The Devil s Right Hand Roadside Magic

Roadside Magic Steelflower at Sea

Steelflower at Sea Agent Gemini

Agent Gemini Blood Call

Blood Call Agent Zero

Agent Zero In The Ruins

In The Ruins Atlanta Bound

Atlanta Bound Hunter, Healer

Hunter, Healer Hunter's Prayer

Hunter's Prayer Roadtrip Z_Season 2_In The Ruins

Roadtrip Z_Season 2_In The Ruins Wasteland King

Wasteland King Pack

Pack Flesh Circus - 4

Flesh Circus - 4 Trailer Park Fae

Trailer Park Fae The Bandit King h-2

The Bandit King h-2 Working for the Devil

Working for the Devil Pocalypse Road

Pocalypse Road Cormorant Run

Cormorant Run Dante Valentine Book 5 - To Hell and Back

Dante Valentine Book 5 - To Hell and Back Desires, Known

Desires, Known Roadtrip Z (Season 3): Pocalypse Road

Roadtrip Z (Season 3): Pocalypse Road Afterwar

Afterwar Selene

Selene The Society

The Society The Hedgewitch Queen h-1

The Hedgewitch Queen h-1 Night Shift jk-1

Night Shift jk-1 Dead Man Rising

Dead Man Rising Dead Man Rising dv-2

Dead Man Rising dv-2 The Iron Wyrm Affair: Bannon and Clare: Book 1

The Iron Wyrm Affair: Bannon and Clare: Book 1 Saint City Sinners dv-4

Saint City Sinners dv-4 Heaven's Spite jk-5

Heaven's Spite jk-5 Beast of Wonder

Beast of Wonder Hunter's Prayer jk-2

Hunter's Prayer jk-2 The Damnation Affair

The Damnation Affair Steelflower

Steelflower The Red Plague Affair: Bannon & Clare: Book Two

The Red Plague Affair: Bannon & Clare: Book Two The Iron Wyrm Affair tb&ca-1

The Iron Wyrm Affair tb&ca-1 Flesh Circus jk-4

Flesh Circus jk-4 Jozzie & Sugar Belle

Jozzie & Sugar Belle Night Shift

Night Shift The Bandit King

The Bandit King![Hunter, Healer [Sequel to The Society] Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/05/hunter_healer_[sequel_to_the_society]_preview.jpg) Hunter, Healer [Sequel to The Society]

Hunter, Healer [Sequel to The Society] The Devil's Right Hand dv-3

The Devil's Right Hand dv-3 To Hell and Back dv-5

To Hell and Back dv-5 Angel Town

Angel Town The Red Plague Affair tb&ca-2

The Red Plague Affair tb&ca-2 Redemption Alley jk-3

Redemption Alley jk-3 The Damnation Affair (the bannon & clare affairs)

The Damnation Affair (the bannon & clare affairs) Working for the Devil dv-1

Working for the Devil dv-1