- Home

- Lilith Saintcrow

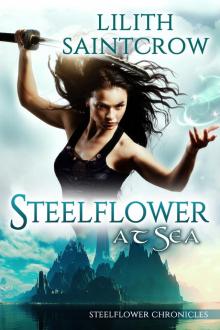

Steelflower at Sea

Steelflower at Sea Read online

Steelflower at Sea

Lilith Saintcrow

Copyright © 2016 by Lilith Saintcrow

* * *

Print ISBN: 978-0989975384

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the author, except for the use of brief quotations in a book review.

For Skyla, who believes.

Contents

1. Blessing, Curse

2. Does Not Bear Mentioning

3. The Rule of Shipboard

4. More in Common

5. Prize Freedom More

6. The Number Makes Him Uneasy

7. A Little Sour

8. Made of Your Metal

9. Much to Chew

10. What Is Owed

11. Dutiful

12. Until You Know

13. A Long Afternoon

14. A Fine Distinction

15. Baffle and Breeches

16. Worth the Coin

17. As A Reed

18. Head of Many Bodies

19. Hospitality

20. Distrustful of Air

21. Reckoned For It

22. And Him They May Not Have

23. Safer If I Were Not

24. Roof Dancing

25. Answers To Give

26. No Songs Of This

27. Straws In Your Storm

28. Certain Proprieties

Glossary

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Blessing, Curse

The fat-sailed high-prowed Taryam’ajak of Antai bit salt swells, singing of rigging and canvas strained by pressure, bound for home across the wide blue desert of the Lan’ai. I braced myself against the railing, ocean’s song stripping my braids back with steady chill fingers. Night on the back of the restless sea-mare folded around me, clouds scudding scarves for the Moon’s silver face and stars filling a sky made limitless by the heaving backs of waves underneath. Even on the Danhai plains, that great grass sea, the sky can drive a Shainakh mad. I had seen more than a few cases of such sickness—kair’la, they call it.

The Taryam dipped his prow and rose, cutting cleanly through a wave. The Antai call their ships he, since they cleave the Lan’ai, that great blue-breasted goddess. Anything at the mercy of such a divine female must, to them, necessarily be a man.

Wave-song, the salt-breath, and the creak of rigging and timber all have a power to calm. Normally I would be in a hammock belowdecks, dreaming of flight as I often did while a-ship. I wanted nothing more than to lose myself in sleep’s foreign country—my eyes were grainy, my shoulders tight as rigging cables, my dotani heavy against my back.

After a battle, sellsword and enlisted soldier alike crave unconsciousness. The Shainakh call that weariness and its product hath’ar lak.

It is also the word for a death of sleepy old age in a bed, surrounded by loved ones.

Every time I closed my eyes, I heard a throat-scouring scream across a dust-choked plain.

“You’re my luck! You can’t leave! The gods told me! My luck will turn against me! Kaia!” Rikyat’s voice, unfurling across the battlefield. The moans of the dying, and the brass-blood smell of battle—

I wrapped my fingers as far as they would reach around the top of the deckrail, whitened knuckles standing out, thread-thin knife scars even paler. My shoulder twinged briefly—the left, where a shallow, newly healed slice reminded me of how close I’d come to being used.

Would it have been so gods-be-damned difficult for a man to ask? There was precious little I would not have done for Ammerdahl Rikyat, had he simply told me what he planned and what was necessary.

“You should be sleeping.” Darik stood beside me, not leaning against the railing, blue-black hair pushed back from his coppery forehead by the wind’s ungentle fingers, the twin hilts of dotanii rising over his shoulders. Even on a merchant ship, travel-stained and weary, he looked every fingerwidth the prince. Heir to the Dragon Throne of G’mai, nephew of the queen, warlord and strategist... and my s’tarei. Me, the only flawed G’mai, the only woman of my kind to travel alone.

Not alone, now. If it was blessing or curse, I could not yet tell. Neither, I suspected, could he.

I shrugged, unclenching my fingers briefly from salt-scoured wood to tuck a stray braid back into its proper place. I would have to thread more twine through the hair-ropes to keep the mass secured. “So should you,” I pointed out, and heard the sharpness. Ever a blade drawn, the edges behind the words just as likely to flay as to lance a boil.

An edge can heal, the Clau say, and healers carry knives. I wondered if a word could do the same. It never seems to.

The stinging wind veered a point or two, spray fanning high as the prow dipped afresh, and I scanned the moonlit surface as if it were the rolling grass of the Plains, and the Danhai tribesmen swimming in its depths, like the sawtooth highfins the Hain make their curative soup from. Rising to strike the unwary, the only warning a curious quiet before the bolts begin to fly or the knifeblade plunges into a sleeping sentry’s throat.

A sellsword learns to sense the moment before violence strikes. At least, if she means to survive.

Slowly, cautiously, Darik slid his right arm around me, his left flattening along my ribs over the shadow of the last strike of our duel in Vulfentown—the duel that had brought me to twinsickness, nearly killing both of us. “All is well, K’li.” A murmur of G’mai poured into the hollow of my ear, sharp consonants and liquid vowels blurring together.

The shortening of my given name as well as the inflection, unbearably intimate, might have spilled a shiver down my back. I denied it. For well over ten winters my birth-tongue had not crossed my lips, until he appeared. Yet it had begun to seem almost natural to use its rhythm again. “I wish I could be so certain.”

“I know. Is that not enough?” He rested his chin atop my head. I am slightly taller than the average G’mai female, broader at shoulder and hip from years of practice and sellswording, any slimness is deceptive. Darik, however, is slightly larger than most G’mai males, which meant he was several weights heavier and a head-and-a-half taller than even an ill-tempered marshcat of a sellsword.

It made him a comforting wall, his boots braced against the deck, moving with me as the ship rolled across the waves. His left hand tensed slightly. He was in the habit lately of touching the scar, where his dotanii had flicked down my ribs and bit.

Each time he did so, I allowed it for a little longer, and a little longer still.

His warmth made rest seem a possibility. The rest of them were bedded down safely enough—Janaire and Atyarik sharing a hammock, Redfist the giant red barbarian bedded in a pile of blankets between two crates carrying goods I didn’t ask the provenance of, Diyan the erstwhile Vulfentown wharf-rat curled against Redfist’s side. I did not blame him, for the barbarian was heat aplenty, even though he smelled somewhat ripe. And, to round out the entire sorry troupe, Gavrin the Pesh minstrel lay wrapped in blankets an arm’s length from Redfist. He dozed, I supposed, between fits of shipsick heaving.

He would no doubt write a grand clanging epic about said sickness and subject us to it as soon as we reached Antai.

I had not slept for three days. And before, on the long ride back to Vulfentown, I had barely rested at all. I had convinced Janaire to keep giving me the taih’adai—the starmetal spheres that would give me the knowledge of how to use Power, the birthright of all G’mai women.

I had only three of the last set of seven taih’adai to endure before I could...what?

It is not battle that unnerves a sellsword most. Tis the waiting. U

ncertainty can breed its own madness. I could not think of a word in Shainakh that fit, nor in the mouth-of-mush that is Hain, or the sibilants of Pesh. There wasn’t even a satisfactory word in G’mai for it.

“Come below, K’li.” Softly, conciliatory, as if he feared I would turn on him. “There is no danger here. When will we reach port?”

I leaned back, into his chest. Two days from Vulfentown and about to hit the Shelt, shallows falling away beneath the Taryam’ajak’s keel. The great swells would start soon, the ship running with the wind, and Gavrin would be even sicker, unless he adjusted.

Sometimes, they did. The first time I had voyaged across the Lan’ai, my own stomach had hated the liquid heaving of unland. “Sixteen days, most likely twenty. The wind and the wave have the say of it, not us.” The proverb sounded different in G’mai. In the tradetongue it is a marvel of succinct sound, two Shainakh nouns and a Pesh loan-verb shortened into the imperative, and a third term nobody could tell the provenance of. In G’mai, it could be phrased four or five ways, each with a different twist, but I was weary and chose the least poetic of them all.

With Darik behind me, the sea’s breath did not seem so chill. Even a sellsword thief worth much red Shainakh gold reaches the limits of endurance, sooner or later. I had not truly rested since Hain, when I’d picked a barbarian’s pocket and found myself pursued.

“Come.” His inflection was gentle, and made the word almost a question instead of a command.

I let him work my fingers free of the rail, his hands callused as mine from swordplay. I let him lead me belowdeck, into our rented corner of the hold. Kesamine at the Swallows Moon Inn had found us passage to Antai on a merchant ship with little fuss. The captain was a Drava’s-kin, and so beholden to Kesa, and the enticement of having four G’mai and a barbarian with an axe made up for the extra useless mouths—a wharf-rat and a minstrel who had already proved to be shipsick. The extra blades I provided would be welcome if unluck in the form of pirates struck.

As for the rest, we’d paid in good red gold. Many thanks to Ammerdahl Rikyat, there was enough and to spare.

My luck will turn against me!

One barred chest wedged against Redfist’s back contained two hundred forty-eight Shainakh red Rams now, a merchant lord’s ransom. I had wanted to dump it in the Shainakh army camp, but Janaire and Atyarik overruled me. By the time we had bedded down that night on the coastal plain, it had been too late to argue.

Better to use the gold than waste it, Janaire said firmly.

I would lose my reputation as a thief if I threw away good red gold for a silly little point of honor, too. Not to mention winter looming, and this small collection of outcasts looking to me for food and shelter.

Perhaps it was my payment for the tangle I found myself in. Solid land turning to sea underfoot, a s’tarei of my own and the birthright of my kind, the one thing I had always lacked, offered to me with open palms. I could not help but peer at the giver and wait for the luck to be snatched away.

Wandering the world had taught me very little is given freely, and that which is often has a sting in the tail.

My own rented hammock swung gently with the motion of the ship, but I dropped my sword-harness to one side and collapsed atop Darik’s sleeping-roll. I fussed with the blankets while Darik unbuckled his own sword-harness and laid it down with finicky precision, lowered himself gingerly beside me.

As long as I had been awake, he had been with me, uncomplaining.

I was too exhausted to pretend, anymore. I waited until he had settled himself; I rolled close to his side, carrying my share of blankets along too. The wooden floor was hard and swaying, but at least there were no stones beneath the sleeping-roll, and with his heat beside me I would not wake in the late watches shivering.

We both kept our boots on. You do not sleep without your footgear unless you are certain.

I much doubted I would ever be certain of anything, ever again.

It took rearranging, but we finally settled, my head on his shoulder, my eyes closed, my arm thrown loosely across his chest, a knifehilt supporting my elbow. Yet another measure of our accord, that we would both sleep with blades to hand.

It is never wise to do otherwise on a ship, even one you may trust the captain of. I learned as much my first stomach-churning time across the Lan’ai, and took the lesson to heart. I still had the scar up my ribs, a skittering knifeblade in the dark and the fear, Mother Moon, the fear.

“There,” D’ri whispered, quietly enough I almost missed the word under the sounds of wood creaking and the gurgle against the ship’s thin wooden skin. “We are all safe, for the time being.”

I nodded, my braids digging into his shoulder. If it was uncomfortable, he made no sign, and I did not feel it. “Thank the Moon,” I murmured, in sleepy G’mai. “My luck is due to be better soon.”

That earned a small laugh, rumbling against my ear. “Rest, Kaia.” His hand came up. I think he meant to stroke my hair, but instead his fingertips found my cheek, and he stopped, calluses barely touching. “Your s’tarei will stand watch.”

“You should...” I could not take him to task as thoroughly as he deserved. I fell into blackness without even a grateful sigh.

Does Not Bear Mentioning

“Hold it so.” I reached over Diyan’s shoulder to correct his grip on the knifehilt. “As if you have a hand clasped in yours. Not so tight; it will be torn away. There. Now, again.”

The afternoon sun glittered; after a slackening at nooning, a freshening wind filled the canvas. The skinny boy pawed dark hair out of his eyes and tried again, an upward slash. “Good.” I moved behind him, pushing him forward. “Never forget your feet. Half a knife-fight is won below the knees.”

“’Ware your side, young one,” pale Rainak Redfist said gruffly, from his easy crouch in the lee of a coiled rope. Sea travel agreed with him. He looked actually happy, his red beard curling with the spray and his bulk more graceful than many a land-dweller could claim to be. It brought out the ruddiness in his floury cheeks as well, and if his leather jerkin was often sodden, he bore it with a smile.

Gavrin the Pesh minstrel, his dirty-straw hair slicked with sweat, heaved desperately over the side. Janaire, her soft Gavridar face expressionless, held her hand over his shoulder. Power rang under her palm, sinking into the young man’s shaking body. “Gods,” he groaned, and added something highly impolite in his native tongue.

Pesh are filthy-mouthed, and former slaves doubly so. Even the sailors were in awe of the minstrel’s command of obscenities in both his own Pesh and tradespeak. Perhaps it was a function of his craft.

Lean long-faced Atyarik sat cross-legged and iron-spined upon the deck next to the copper-furred barbarian, watching me teach the boy. He occasionally glanced at Janaire, but she had the minstrel well in hand. The Northern giant and the Tyaanismir s’tarei understood each other in the way of old sellswords, and their ease with each other relieved me of any responsibility to speak overmuch to either of them.

Still, it irked me, a little. Since I’d picked Redfist’s pocket that night in Hain, I hadn’t had a moment’s comfortable solitude, but...well, I almost missed the forest and only a giant Northerner causing me problems, instead of a group of lagging sheep to feed, clothe, and care for. That the sheep preferred their own society to mine was to be expected, but still.

The wind bore no shrieking, yet beaten-iron clouds raced on either side. The crew were all nervous, smelling change. If the clouds closed on us, most of my charges would be belowdecks while a storm tossed the ship about. “Good,” I told the boy, and he preened. Salt air, free movement, and a larger supply of food had done wonders for his frame. He had grown like a mirinweed these past few weeks, though how much of that was his laying aside the wharf-rat habit of slouching in shadows I could not guess. He also hid small bits of travel-bread, or salted meat, in his pockets until they moldered.

Hunger does strange things, especially to the young. I pretended not to n

otice, and he sometimes, shamefaced, crept to the railing to drop the crumbling bits into the Lan’ai’s embrace. “Now, hold like so, step with your foot thus, and move here. Good. Again.”

He obeyed with good grace, but as soon as he started, a shout rose from portside. I straightened swiftly, almost knocking the boy over, set him on his feet with absent care. Even growing, he was still a slight lad.

Darik, his hands occupied with a whetstone and a slightly-curved smallknife, glanced at me.

“Keep going,” I told the boy. “D’ri, drill him?”

He nodded, pushing straight black hair from his severely beautiful Dragaemir features. I would find a means of trimming his mane soon as we approached land. An adai’s duty, one I had neglected as I had so many others. There was much to berate myself for, should I ever decide to start doing so in earnest.

I negotiated the slippery wood to the captain’s deck, waited for Hrufel’s nod of acknowledgement, and climbed up the three last stairs to his unchallenged fiefdom. “Ai,” he growled at his adjii, and added something I might have blushed to repeat, lowering a farlooker of wood, brass, and ground glass. I followed his line, almost turning my back to him.

But not quite.

G’mai have excellent vision. Three specks, moving fast with the wind, bearing down on us. My heart sank. “That does not seem a merchant convoy.”

Hrufel grunted and handed me the farlooker, its leather case dangling from a strap at his belt. I peered through, though I already suspected what I would find.

Incorruptible

Incorruptible Finder (The Watchers Book 6)

Finder (The Watchers Book 6) Steelflower in Snow

Steelflower in Snow Dante Valentine

Dante Valentine Redemption Alley-Jill Kismet 3

Redemption Alley-Jill Kismet 3 The Iron Wyrm Affair

The Iron Wyrm Affair The Demon's Librarian

The Demon's Librarian The Hedgewitch Queen

The Hedgewitch Queen Redemption Alley

Redemption Alley Flesh Circus

Flesh Circus Saint City Sinners

Saint City Sinners Unfallen

Unfallen Heaven’s Spite

Heaven’s Spite The Devil s Right Hand

The Devil s Right Hand Roadside Magic

Roadside Magic Steelflower at Sea

Steelflower at Sea Agent Gemini

Agent Gemini Blood Call

Blood Call Agent Zero

Agent Zero In The Ruins

In The Ruins Atlanta Bound

Atlanta Bound Hunter, Healer

Hunter, Healer Hunter's Prayer

Hunter's Prayer Roadtrip Z_Season 2_In The Ruins

Roadtrip Z_Season 2_In The Ruins Wasteland King

Wasteland King Pack

Pack Flesh Circus - 4

Flesh Circus - 4 Trailer Park Fae

Trailer Park Fae The Bandit King h-2

The Bandit King h-2 Working for the Devil

Working for the Devil Pocalypse Road

Pocalypse Road Cormorant Run

Cormorant Run Dante Valentine Book 5 - To Hell and Back

Dante Valentine Book 5 - To Hell and Back Desires, Known

Desires, Known Roadtrip Z (Season 3): Pocalypse Road

Roadtrip Z (Season 3): Pocalypse Road Afterwar

Afterwar Selene

Selene The Society

The Society The Hedgewitch Queen h-1

The Hedgewitch Queen h-1 Night Shift jk-1

Night Shift jk-1 Dead Man Rising

Dead Man Rising Dead Man Rising dv-2

Dead Man Rising dv-2 The Iron Wyrm Affair: Bannon and Clare: Book 1

The Iron Wyrm Affair: Bannon and Clare: Book 1 Saint City Sinners dv-4

Saint City Sinners dv-4 Heaven's Spite jk-5

Heaven's Spite jk-5 Beast of Wonder

Beast of Wonder Hunter's Prayer jk-2

Hunter's Prayer jk-2 The Damnation Affair

The Damnation Affair Steelflower

Steelflower The Red Plague Affair: Bannon & Clare: Book Two

The Red Plague Affair: Bannon & Clare: Book Two The Iron Wyrm Affair tb&ca-1

The Iron Wyrm Affair tb&ca-1 Flesh Circus jk-4

Flesh Circus jk-4 Jozzie & Sugar Belle

Jozzie & Sugar Belle Night Shift

Night Shift The Bandit King

The Bandit King![Hunter, Healer [Sequel to The Society] Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/05/hunter_healer_[sequel_to_the_society]_preview.jpg) Hunter, Healer [Sequel to The Society]

Hunter, Healer [Sequel to The Society] The Devil's Right Hand dv-3

The Devil's Right Hand dv-3 To Hell and Back dv-5

To Hell and Back dv-5 Angel Town

Angel Town The Red Plague Affair tb&ca-2

The Red Plague Affair tb&ca-2 Redemption Alley jk-3

Redemption Alley jk-3 The Damnation Affair (the bannon & clare affairs)

The Damnation Affair (the bannon & clare affairs) Working for the Devil dv-1

Working for the Devil dv-1